3. Display Content Clearly on the Page

Introduction

Writing easy-to-read web content is only the first step. If you want

people to understand the content, it needs to look easy to read—both

on desktop and on mobile.

Even health content written in plain language can look overwhelming if

there’s too much text in a paragraph or not enough space on the

page.7,24,35,49

And if your site doesn’t display or function well on mobile, users on

mobile devices may give up before they even get to your content.

Web design and content go hand in hand. Use white space, layout, font,

and color to help users understand the content on your website.

Try this

When developing your health content, imagine you’re

writing for a mobile screen. This will naturally force you to take into

account many of the best practices outlined in this section. By writing

for a mobile display, your content will be simpler and easier to

understand across all screen sizes.

3.1 Limit paragraph size. Use bullets and short lists.

It’s very important not to overwhelm your users with content regardless

of screen size. These principles apply not only to mobile devices, but

to desktops and laptops as well. All of the following can trigger web

users with limited literacy skills to skip over content:

- Dense “walls” of text

- Long sentences

- Paragraphs with multiple numbers in the text

- Long words

- Paragraphs with more than 3 lines7,24,28

The takeaway here is that users will skip information that looks

difficult to read regardless of how simply it’s written or how important

it is.

Additionally, write for users’ limited working memory. Breaking up

content into manageable “chunks” or bulleted or numbered lists can help.

For example:

- Use clear, stand-alone sections or “chunks” of text with

headings.24,30,53

- Make sure each chunk of text has only 1 theme or

idea.54

- Turn sentences into lists when possible.24,30

- If your list has more than 7 items, break it up into several

sub-lists.54

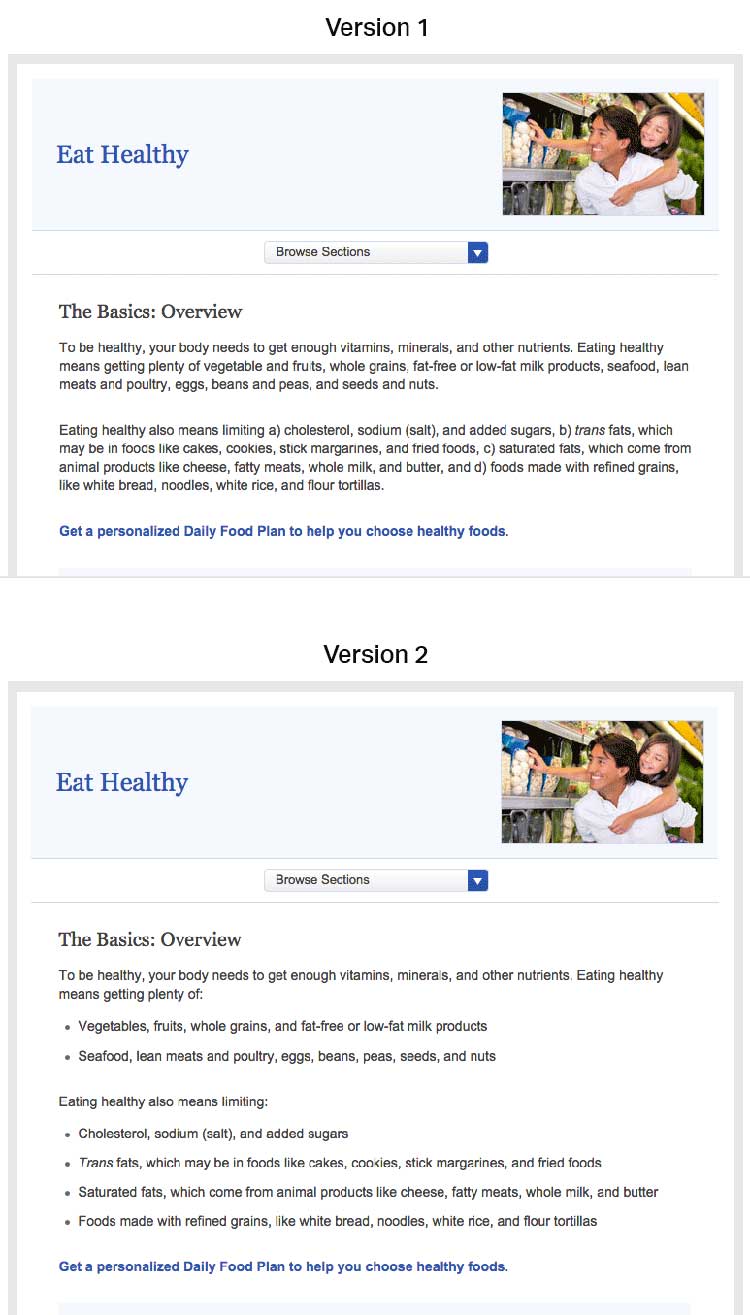

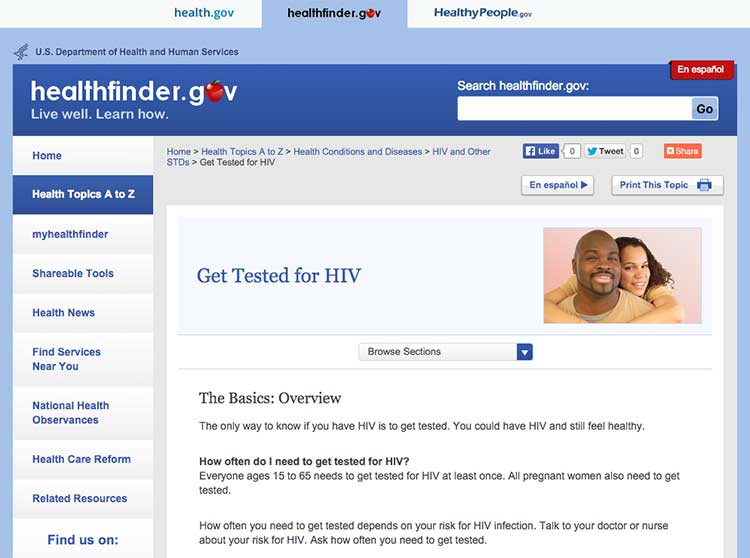

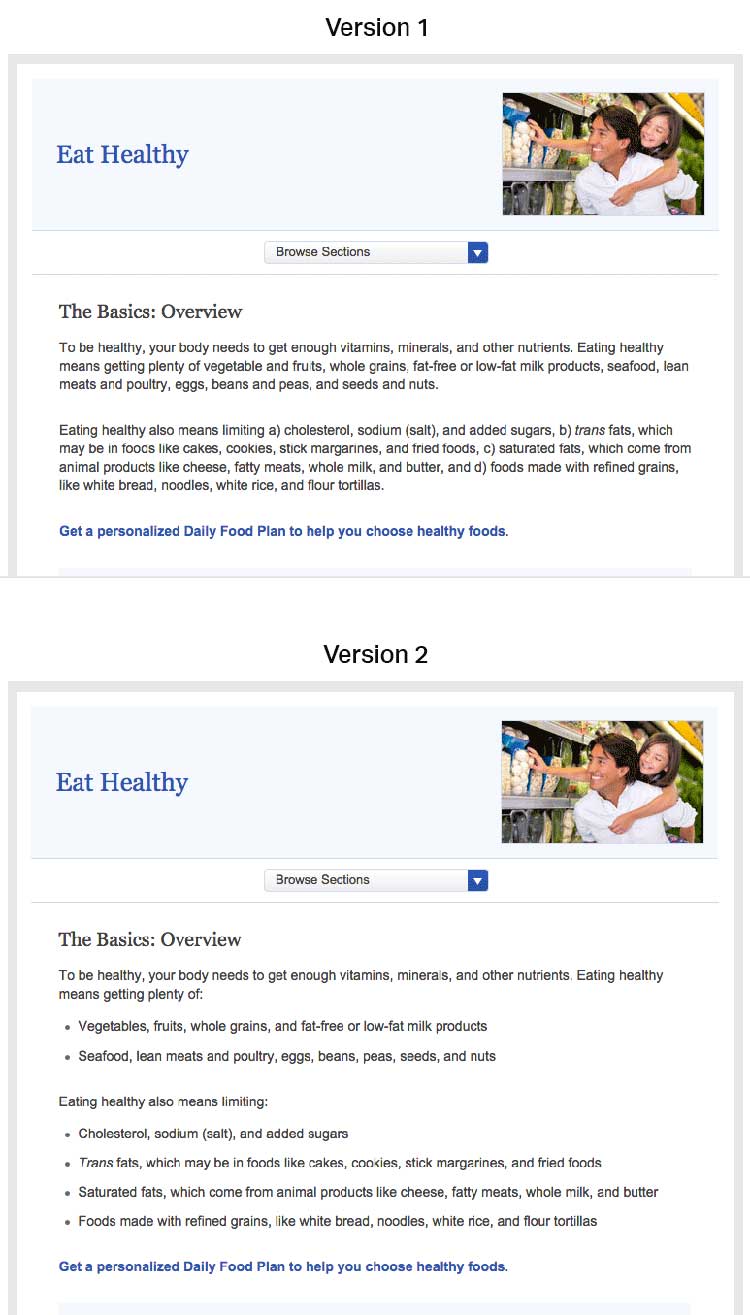

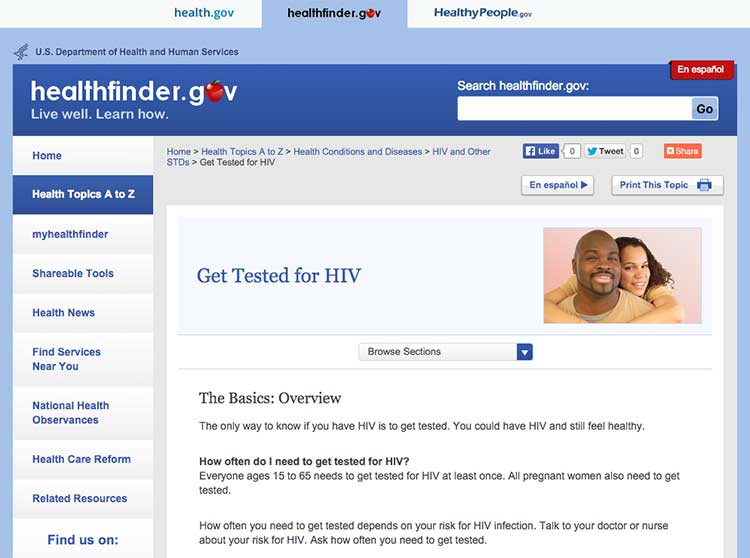

Figure 3.1

Compare these webpages from healthfinder.gov. Users are less

likely to read content presented in long paragraphs of text, as in

version 1. Version 2 is easier to read because it uses bulleted lists

and smaller “chunks” of text.

3.2 Use meaningful headings.

When users scan webpages, they often only read the headings to figure

out if the content is relevant to them. It’s important to make your

headings as specific as possible24,30—try to include keywords to help

users find the information they need.

Including keywords in headings also makes it more likely that search

engines will show your content in search results. Search engines show

sites where keywords appear in the web address, title, page headings,

and links before they show websites with keywords that only appear in

content.

Try this

Start headings with verbs when you can. This helps set you

up to write actionable content.

Use subheadings.

Adding a subheading, or “teaser” text, underneath each heading can give

the user additional clues about what to expect from your content.

Suggestion

Main heading: Get Active

Subheading: Aim for 2 hours and 30 minutes of activity a week.

Consider question headings.

When appropriate, try using questions as headings.24 Use “I” and “me”

to reflect the voice of the user.

For example, when discussing mammograms, common questions include:

- How will this benefit me?

- How much does it cost?

- What happens if the doctor finds something wrong?

- How often do I need to get tested?

- Does it hurt?

- Are there any risks associated with the test?

- What if I don’t have time?

Place headings properly.

Make sure your headings don’t “float” on the page (floating happens when

there’s too much white space above and below the heading). Make it clear

which chunk of text the heading corresponds to—leave more space above a

heading than between the heading and the text that comes after it.24

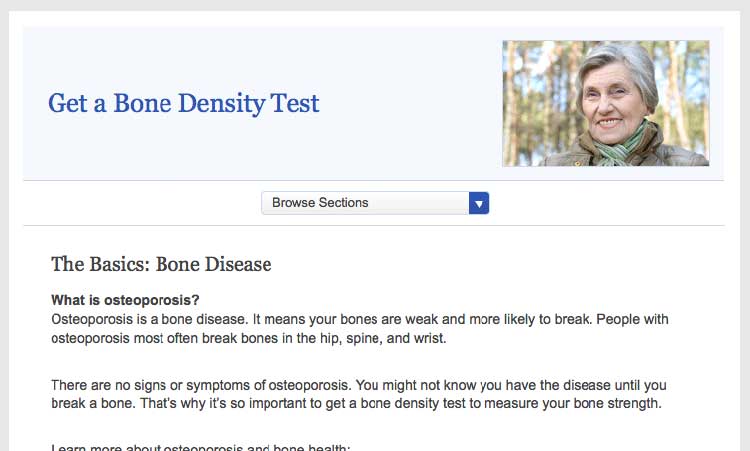

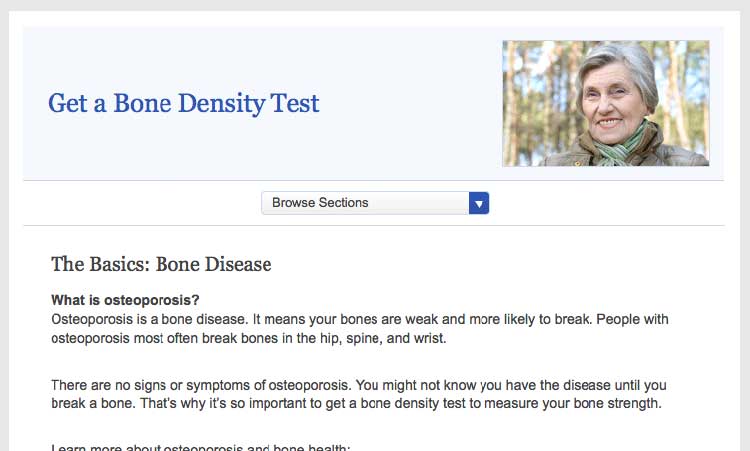

Figure 3.2

On this healthfinder.gov webpage, information about

osteoporosis is organized using questions as headings. There’s more

space before the heading than after, creating clear “chunks” of text.

3.3 Use a readable font that’s at least 16 pixels.

The font you choose is important because it affects your site’s

readability. Below, we list the most important elements that contribute

to making a font readable.

Size

Choose a font that’s at least 16 pixels, or 12 points. If many of your

users are older adults, consider using an even larger font size—19

pixels or 14 points.6,24 A small font size is more

difficult to read, especially for users with limited literacy skills and

older adults.

Quote

Quote

“I like when I can read the words without my

reading glasses.”

Set up your site so that users can adjust the size of the text on the

page.24 Web designers can make this possible by using what’s called

relative type size. However, it’s still important to test out your

website with different font sizes to make sure it’s still easy to read

and navigate. Always check how your content looks on a mobile device, as

well—newer, high-resolution screens that render more pixels per inch can

make text look smaller.

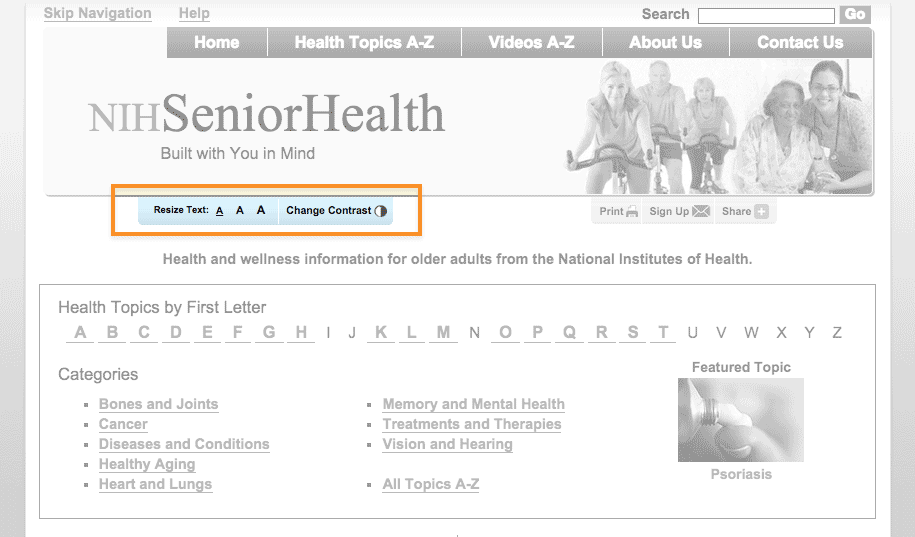

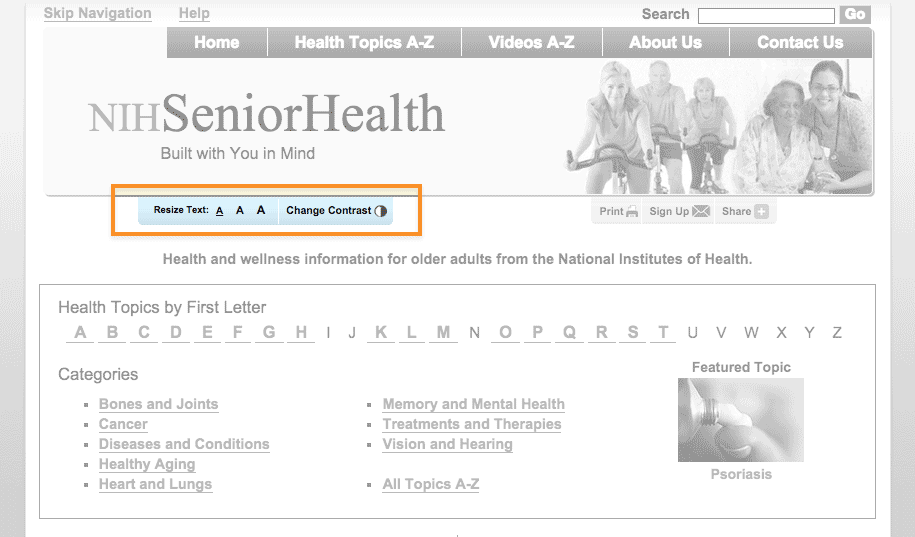

Figure 3.3

NIH SeniorHealth includes a toolbar on every page that allows

users to change text size and adjust color contrast (colored text on a

black background).

Simplicity

Unusual fonts with unnecessary flourishes can be hard to read. Choose a

mainstream font that will feel familiar to your users.30

It’s easier to read text printed in simple, familiar fonts like

Verdana.

Example

Lucida Handwriting

“Regular physical activity is good for your health. Get tips to help you

get more active.”

Verdana

“Regular physical activity is good for your health. Get tips to help you

get more active.”

Also, while you can use a different font for headings and body content, don’t use more than 3 fonts on a page. Use fewer, simpler fonts to make your page look more cohesive.55

Serif or sans serif?

There’s been a lot of debate about which type of font is easier to read

online—and overall, the research is inconclusive.30,56

However, some evidence suggests that serif fonts may make reading on the

web more difficult for users with reading

disorders.56,57

The bottom line: Choosing sans serif fonts is best practice when writing

for the web.24,57,58 Use a familiar sans serif font like

Verdana, Lato, Open Sans, Proxima Nova, or Source Sans.

Line height

Line height (also called leading) is the vertical distance between lines

of text. Common line heights in word processing include:

- “Single spaced” (line height of 100%, equal to the font size)

- 1.5 lines (line height of 150%, equal to 1.5 times the font size)

- “Double spaced” (line height of 200%, twice the font size)

Some word processors—and many web design programs—will give you even

more options.

To maximize readability, use a line height that is 130% to 150% larger

than the font size.56 This helps keep users with limited literacy

skills from losing their place in the text as they start reading a new

line—and makes it easier for them to use their fingers to help keep

their place.

Example

It’s best to specify leading of about 140% (the middle option

below).59

100% Leading

“Making small changes to your eating habits can make a big difference

for your health. Here are some tips and tools you can use to get

started.”

140% Leading

“Making small changes to your eating habits can make a big difference

for your health. Here are some tips and tools you can use to get

started.”

200% Leading

“Making small changes to your eating habits can make a big difference

for your health. Here are some tips and tools you can use to get

started.”

Line height is also an important consideration for mobile users. When

paragraphs or bulleted lists include multiple links, extra height

between lines helps ensure that users have enough room to tap the item

they want.60

3.4 Use white space and avoid clutter.

Clean, uncluttered webpages are easier to read24,30—they’re less

distracting and less overwhelming for everyone, especially people with

limited literacy skills and very busy users.

Use white space in your content to break information into chunks. Leave

space between sections of text and around images and buttons.

Figure 3.4

The CDC.gov homepage includes space around the logo and search

box, and under the banner image, which helps the site look clean and

uncluttered.

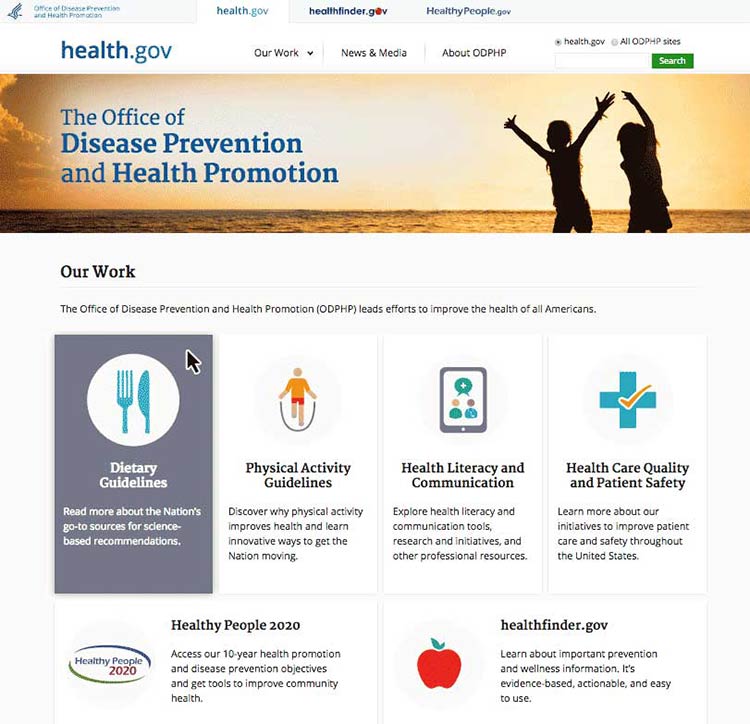

Figure 3.5

The health.gov homepage also has a very clean look with lots of

white space.

White space around site features also helps mobile users interact with

buttons and links without accidentally tapping the wrong place.

3.5 Keep the most important content above the fold—even on mobile.24,30,61

Users spend the most time looking at content they see

first,62 so make sure the most important and compelling

content appears above the fold. Users also judge the content they can

see to decide whether it’s worth scrolling down to see more.62

Figure 3.6

The most important content in this topic about getting tested

for HIV is visible above the fold.

Keep in mind that low literacy readers may have trouble with

scrolling—eye-tracking data shows that the need to scroll makes it more

likely that they’ll skip content as they try to find their place again

to continue reading. That’s why it’s important to minimize scrolling

when you can.63

If your content continues below the fold, the best cue to let users know

they need to scroll down is a paragraph of text that crosses the scroll

line.64 However, it’s very challenging to ensure that

this will display consistently on different screen sizes—so you may want

to consider using a scroll arrow or scroll bar

instead.65

Try this

View your website using different monitors, browsers, and

devices to see how your content displays on the screen.

Finally, be aware that users may mistake horizontal lines or large

sections of white space at the bottom of their screen for the end of a

webpage. That’s a good reason to look at your site on many devices and

screen sizes. If you find either of these at the bottom of a page,

consider making some changes—“false bottoms” might stop people from

seeing all of your content.24

3.6 Use links effectively.

The ability to link to related content is a major benefit of writing for the web. Below, we list some strategies for using links effectively in your online health content.

Limit the number of links on a page.

Users with limited literacy skills sometimes click on links instead of reading content on a page.7 Limiting how many links you have on a page can help prevent too much “link hopping”.

Think about links as exit points—include them only in places where you really want your users to exit.

Link directly to tools and resources that support your

content.28,40

Include links that allow

users to “drill down” for more detailed

information8,28,40—avoid linking to pages with

redundant content.

Here are 3 rules to follow when writing links on a webpage:30

1. Make links long enough to “grab” easily.24,50 If

your link is too short, it may be hard for users to tap or click on the

right part of the screen to select the link.

2. Use descriptive link labels so there are no surprises.24,30

Descriptive link labels tell your user what to expect from a link. Users

should never be surprised by what they find when they click on your

link. They can also help users find the right content—and improve search

engine rankings.

3. Use action verbs in link labels.8,24 Choose actionable link

labels, like “Check out these tips for getting active,” “Find out how to

eat healthy during pregnancy,” or “Read more about diabetes.” Action

verbs help users engage with your content.

Suggestion

- Before:

- Insurance Plan Locator

- After:

- Find the right insurance plan for you

Figure 3.7

Links on this healthfinder.gov webpage follow all 3 rules for

link labeling. Readers know what to expect when they click on each link.

Never use general link labels—they don’t help people know what to

expect. For example, avoid the following link labels:

- Click here

- Print

- Learn more

3.7 Use color or underline to identify links.

Display links so users will easily recognize them as clickable—and stay

consistent with presentation throughout your site.66

To follow established guidelines for displaying links:

- Use blue for unvisited links and purple for visited links unless you

have a reason to choose different colors.

- Test your color choice to make sure it stands out from the body text—and

that it’s visible to people who are color blind.50

- Underline links in main content areas—users still recognize underlined

content as a hyperlink indicator (especially users with low vision or

other accessibility issues).67

- Don’t underline items like navigation menus if their location makes it

clear that they’re links.50

Figure 3.8

NIH Senior Health uses standard link guidelines—blue and

underlined for unvisited links, and purple for visited links.

3.8 Use images that help people learn.

Including simple visuals to support written text can help users with

limited literacy skills find, understand, communicate, and use health

information.30,38,65,68,69

Choose images that support your text.

Think of graphics as a way to enhance and explain your content, not as

decorations. Also look out for visuals that might actually diminish your

content—busy, bright, or animated graphics are distracting and often

mistaken for advertisements.41

Choose realistic images.

Use realistic pictures to illustrate health behaviors and clarify

medical concepts. Users prefer photographs of “real” people rather than

illustrations or people who look like models.49 It’s also important to

show people of diverse racial and ethnic backgrounds. That way, more

people will be able to find “themselves” on your site—and more easily

relate to your content.

Keep in mind that people react strongly to images, so be sure to test

your site with images included. Pay attention to users’ reactions to the

images—they may surprise you.

Try this

When illustrating an anatomical or medical concept,

consider a simple line drawing—they’re often most effective.67

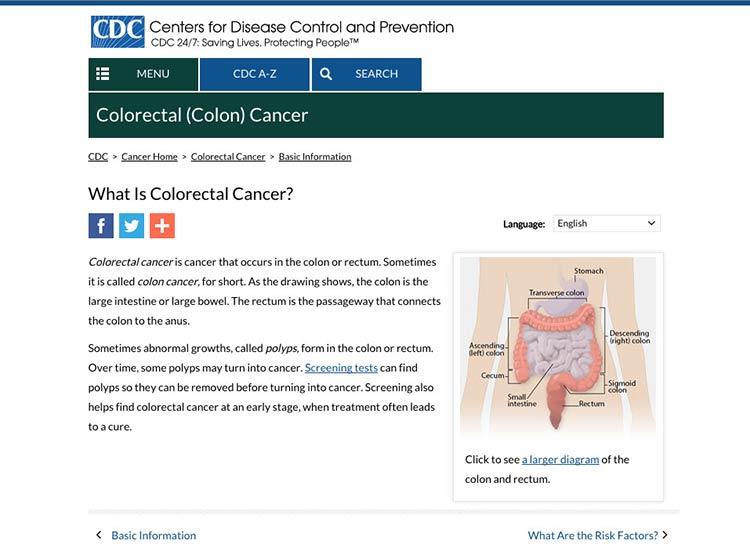

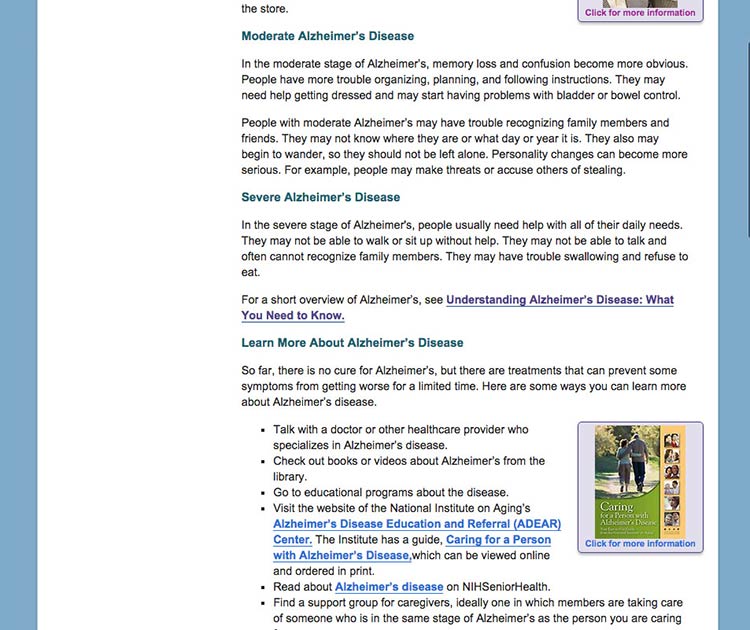

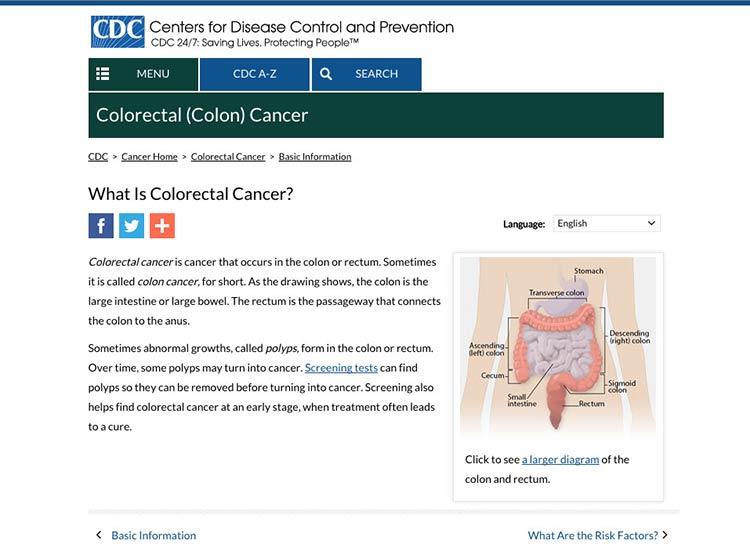

Figure 3.9

This simple line drawing and labels from CDC.gov explain the

location of the colon and rectum.

Make sure the meaning of your image is clear to all users.

Always include a descriptive caption that explains the picture.67 Use

alternative text (called an “alt tag” or “alt text”) to describe

graphics for people using screen readers.

3.9 Use appropriate contrast.

Dark text on a white or very light background is the easiest to

read.24,30 Use reversed-out text (dark backgrounds with light text)

sparingly. It’s also important to keep the background clear, so avoid

patterns and images.

Example

- Good contrast:

- Arteries are the tubes that carry blood away from your heart. Every time your heart beats, it pumps blood through your arteries to the rest of your body.

- Bad contrast:

- Arteries are the tubes that carry blood away from your heart. Every time your heart beats, it pumps blood through your arteries to the rest of your body.

3.10 Make web content printer friendly.

Many web users with limited literacy skills prefer to print pages from a

website rather than read text on a computer screen.28,30,60,65 They may

also want to share health information with family members or friends who

don’t have access to a computer or post it on their refrigerator. That’s

why it’s important to make sure your content is ready to print.

Figure 3.10

When a user clicks the “Print” button, a printer-friendly page appears. The printer-friendly version has clear headings and doesn’t include page numbers.

Quote

Quote

“I would like to print this page and show it to

family members who need this information.”

Use print links for pages designed specifically for printing.

For pages meant to be printed (like a list of questions to bring to the

doctor’s office), prompt users with a print link. Make the print link or

icon clearly visible on each page. If possible, give users the option to

print a single page, a complete section, or just a portion of the text.

Make printed content user-friendly.

Follow these design guidelines:

- Use a lot of white space, good color contrast, and clear headings on

each page.

- Specify a print style sheet that will only be used when the user

clicks to print the page.

- Design your site with fluid, percentage-based widths that allow for

printing from a range of devices.

- If your site has page numbers, make sure that printing will override

them—or give users a “view all pages”

option.71,72

3.11 Make your site accessible to people with disabilities.

All Federal Government websites must be accessible to people with

disabilities. This is often called Section 508 compliance (referring to

Section 508 of the Rehabilitation

Act).73

The guidance in Section 508 helps us design websites that work for

everyone.

Here are a few of the important considerations addressed under Section

508:

- Make sure screen readers and other assistive technologies can read

your site. That way, users with physical impairments will still be

able to access your content. Usually, this involves confirming a

logical reading order of your page, making sure important content is

near the top of what the screen reader will “see” first, and making

sure that images have appropriate alt text. You can find other

criteria in the Web Content Accessibility Guidelines (WCAG)

2.0.

- Mark up page titles and section headings consistently. This will

ensure that users with and without a screen reader can easily

identify the major content sections on the page.

- Check that users can navigate your site using only a keyboard.

That way, your site will still be accessible for users who have

mobility or vision impairments and aren’t comfortable using a mouse

or touch screen.

- Choose strong color contrast, especially for buttons. Many users

with vision impairments are not actually blind, but rather have low

vision or color blindness. For these users, it’s very difficult to

tell the difference between similar colors—low-contrast text

may disappear.

- Test content that requires the use of plug-ins or dedicated

software for accessibility.30 There are additional accessibility

requirements for other plug-ins that take a user out of a

web browser. It’s important to test non-HTML elements in their

application to make sure they are still accessible to all users.

Get more information about web accessibility

from the Web Accessibility Initiative.

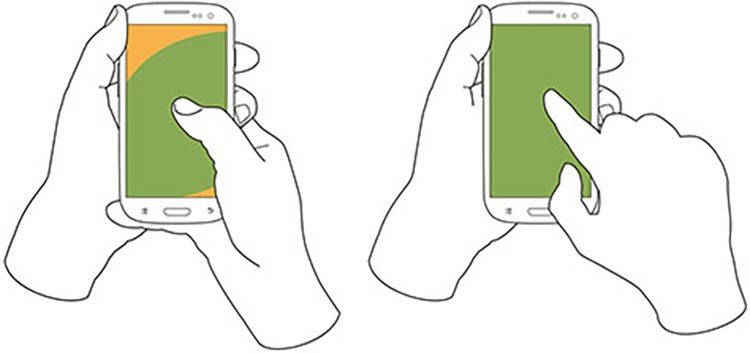

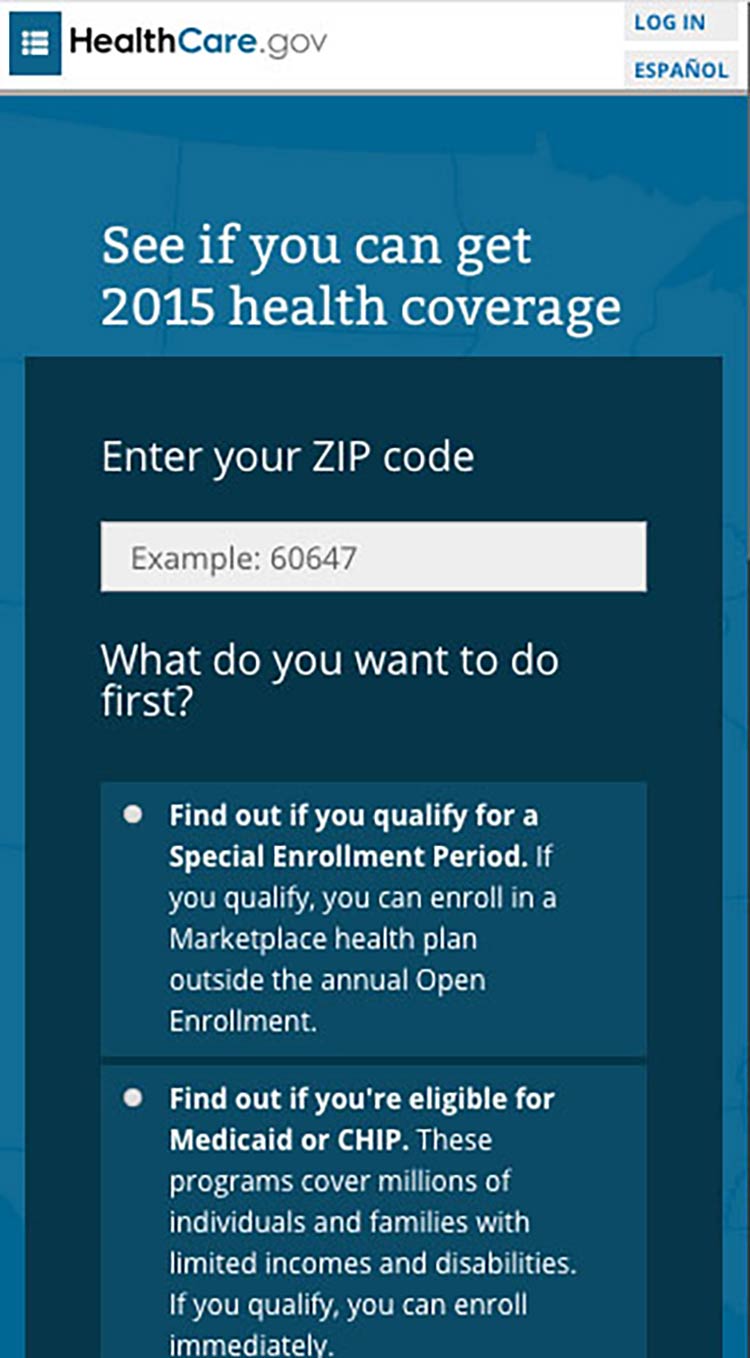

3.12 Make websites responsive.

Today’s users expect websites to work well on every screen they

touch—whether it’s a phone, a tablet, a desktop computer, or whatever

else we haven’t thought of yet. More and more, users are accessing the

web from mobile devices. And for some—especially low-literacy

users—mobile devices may be their only means of web

access.17

With this shift in how we’re accessing web content, web designers have a

variety of options for serving content to mobile users, including native

mobile apps, web apps, and mobile

websites.74,75

For most health websites, responsive design is the best choice.

Responsive design websites show users content in a format that’s

tailored to the screen size, platform, and orientation of the user’s

device.72,73

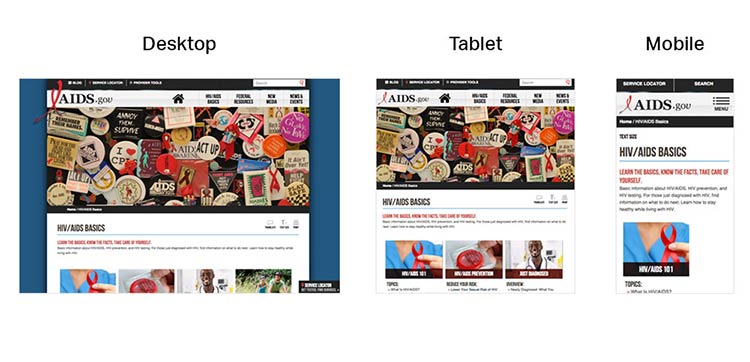

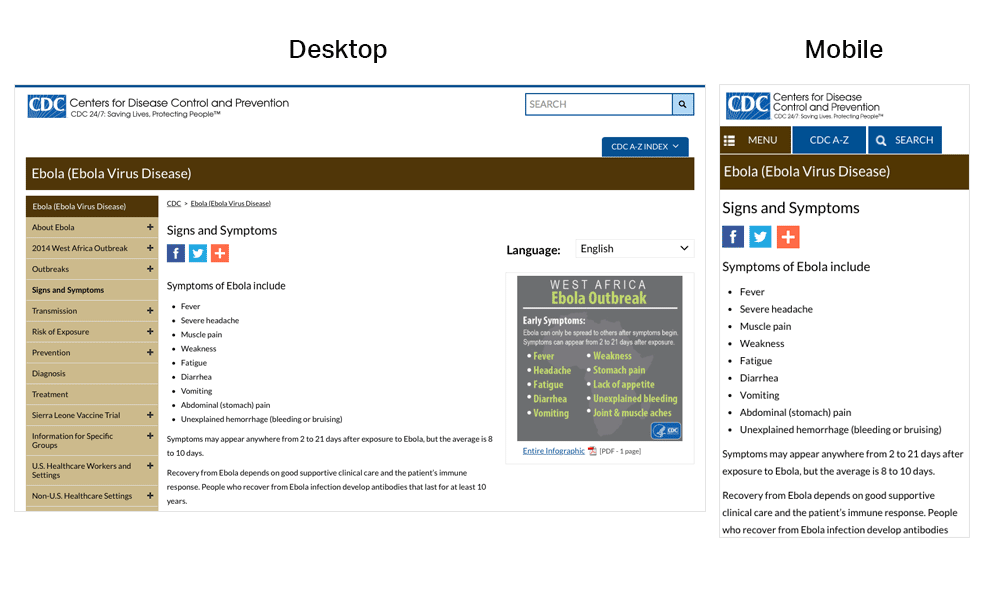

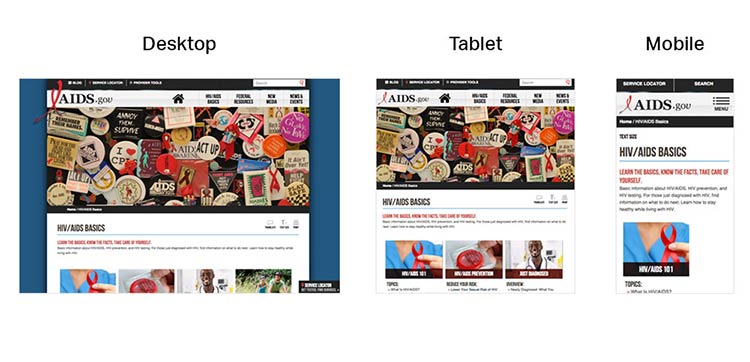

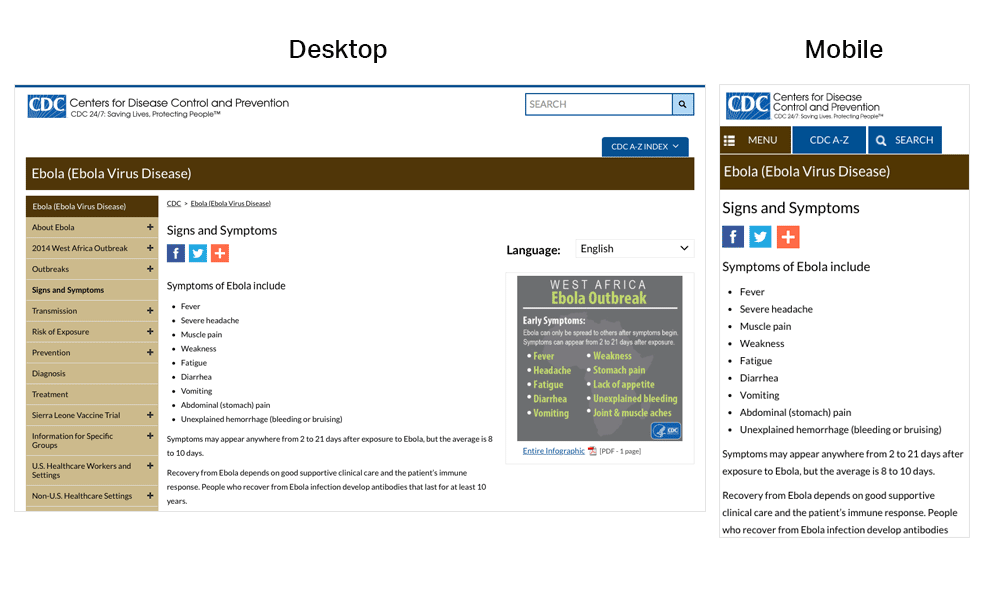

Figure 3.11

AIDS.gov’s responsive design delivers content in different

formats based on the user’s screen width.

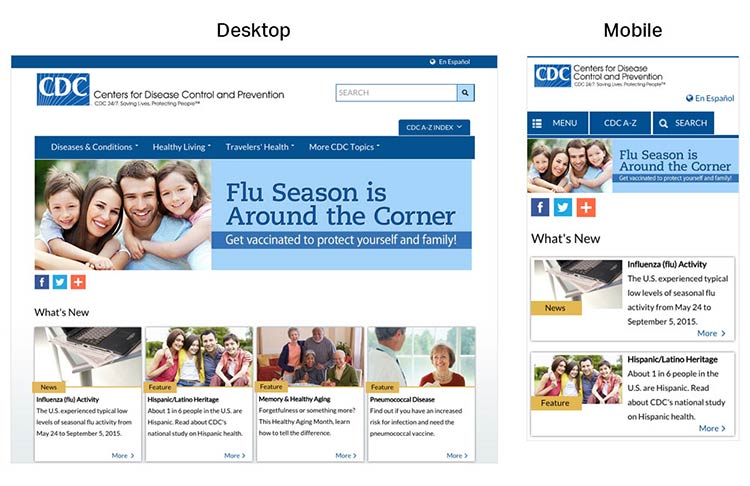

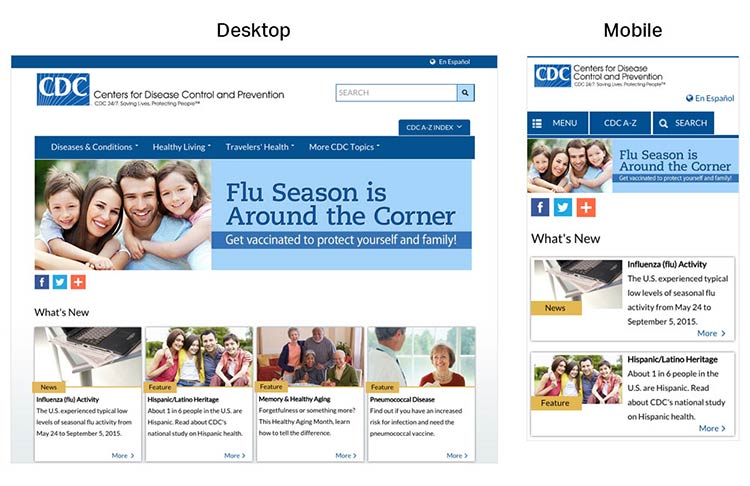

Figure 3.12

CDC’s responsive design template offers a good experience for

users on mobile. The site is reprioritized so that users don’t need to

“pinch” or zoom into content when they land on the page.

A main advantage of responsive design is that a single website can

deliver content optimized to appear on a wide variety of devices and

screen sizes. But keep in mind that responsive design is limited in that

only format—not content—can be tailored based on a user’s device. That’s

why it’s so important to develop content for the smallest screen size.

By doing so, content developers must make tough choices and create a

thoughtful, logical content hierarchy and cut (or link to) superfluous

information.

Most of the time, users won’t think about how your site was built—they

just want a seamless experience across devices.72

3.13 Design mobile content to meet mobile users’ needs.

Many of the core design principles in this guide apply to mobile design

as well as desktop, but there are some additional things to consider

when designing on mobile.

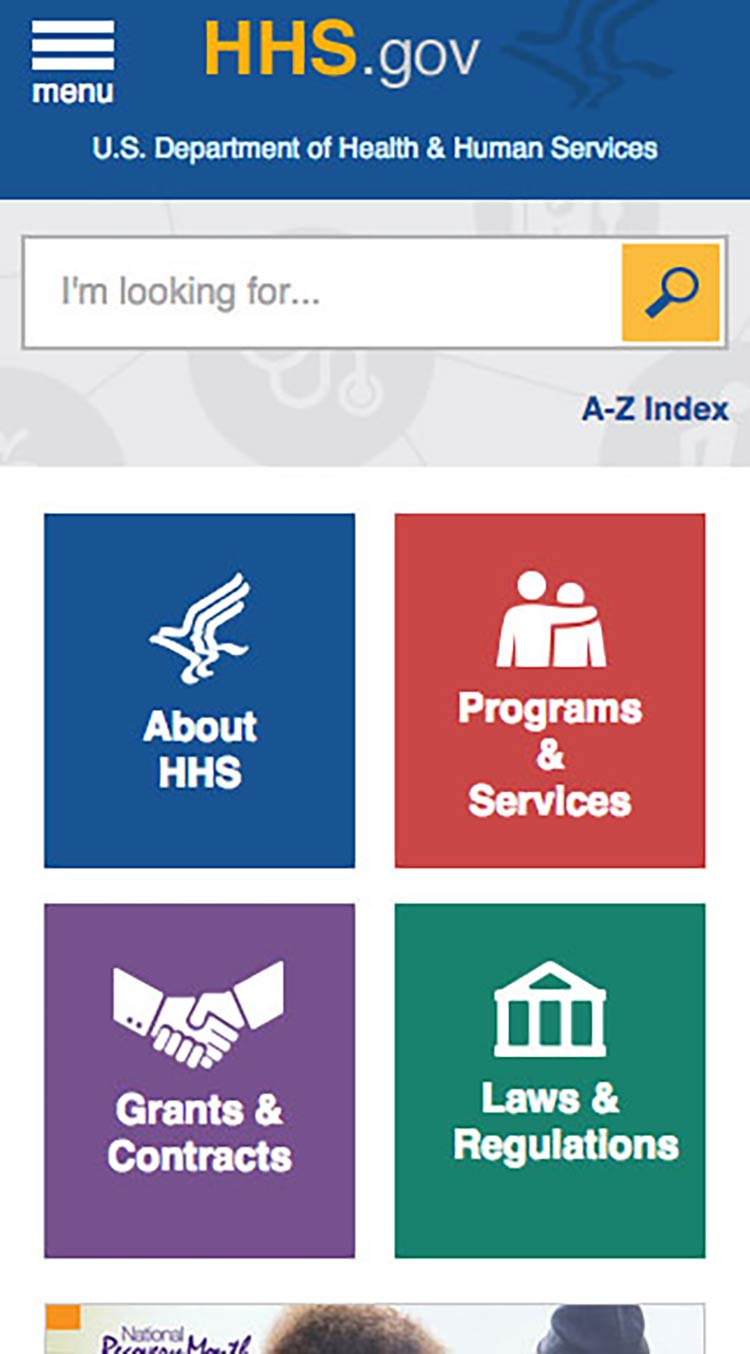

Limit the number of elements on each screen.76

Keeping your design uncluttered is especially important for mobile users

who are viewing content on a small screen. Simple screens enable users

to find what they’re looking for more efficiently.

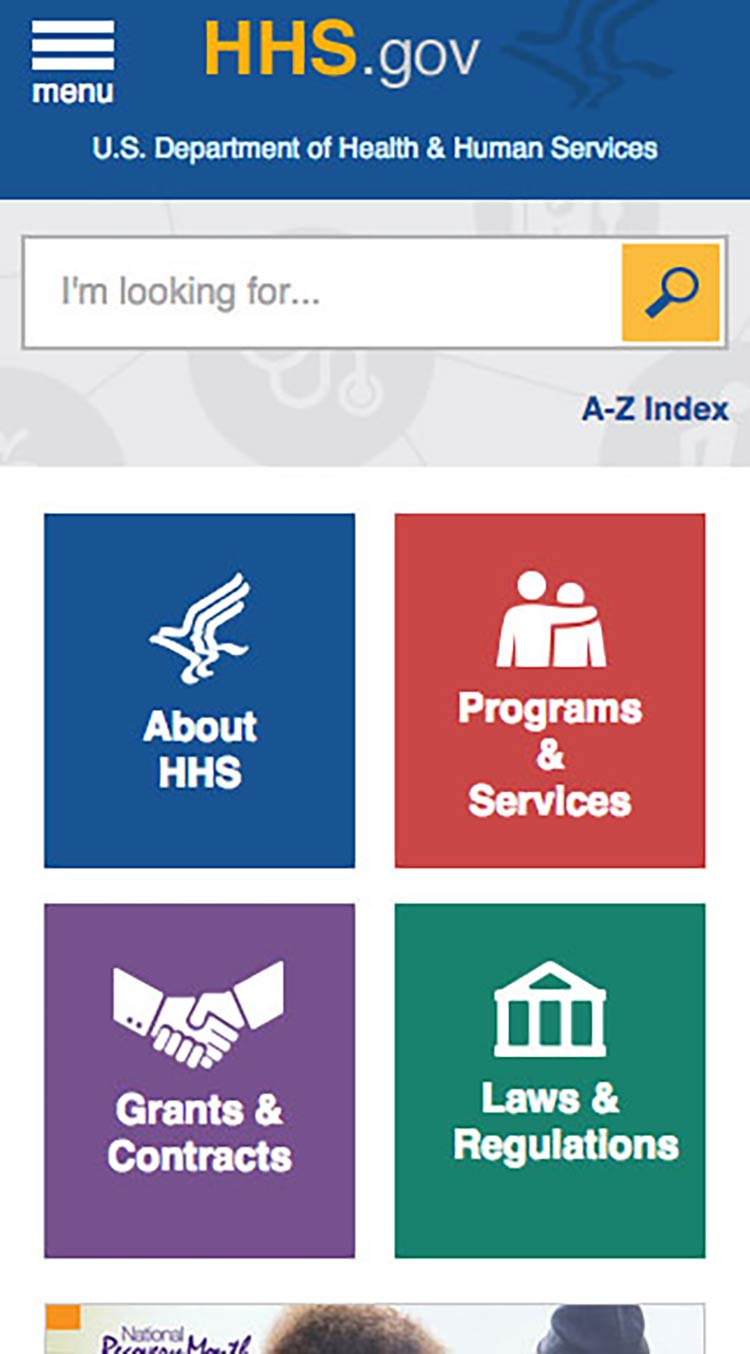

Figure 3.13

On mobile devices, the HHS.gov homepage features a simple

search bar and 4 buttons, each linked to a secondary page.

Prioritize content and features at the top of the page.

Users spend the most time looking at content near the top of the

page.77 Give limited space to elements users interact

with at the top of the page—like buttons, menus, and links—so there’s

room for content.78

Figure 3.14

On mobile devices, the CDC website prioritizes important

content at the top of the page—images and additional settings (like

language preference) are at the bottom of the page.

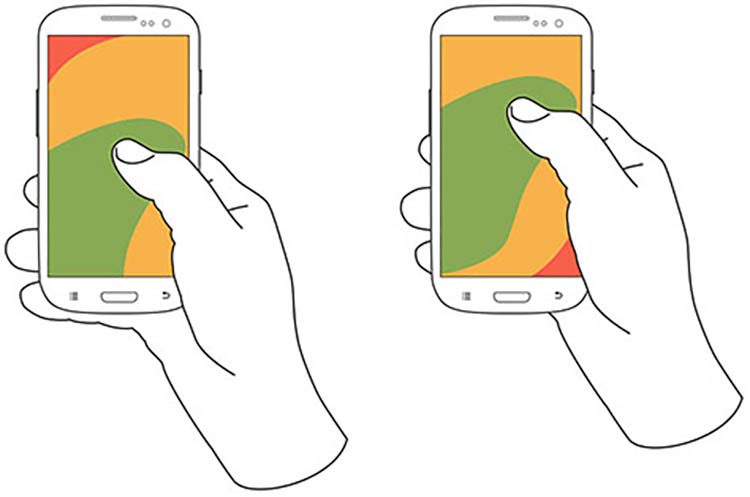

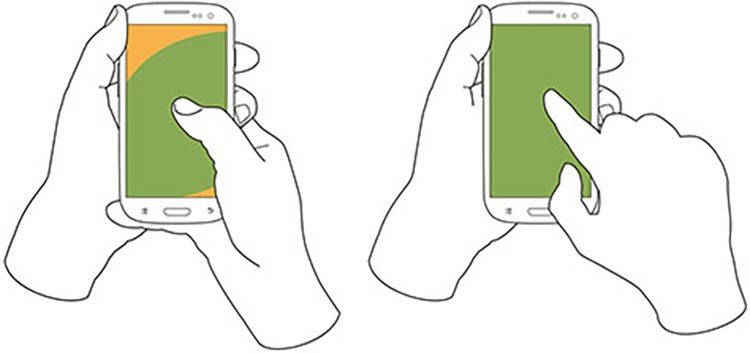

Make interaction easy.

Mobile devices have smaller screens, so selecting a button or typing may

be more challenging than on a desktop computer. Additionally, mobile

interfaces can be challenging for users with physical conditions that

affect their fine motor control (how precisely they can click or touch

things).

With this in mind:

- Limit the amount of text your users need to type.20

- Use large buttons and tappable areas so that people using small devices

can easily select them. Also be sure to include enough space around

them.11,17

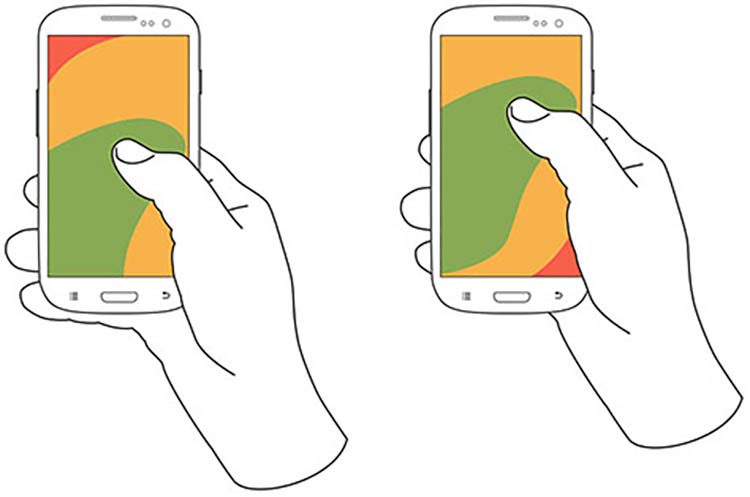

- Place frequently used buttons where they’re easy to reach. The easiest

places to reach depend on the size of the device and how the user is

holding it. In most cases, the center and bottom of the screen are

easier to reach than the top.17,79

Figure 3.15

Users hold their phones in various ways, but the center and

bottom of the screen are usually easiest to reach.

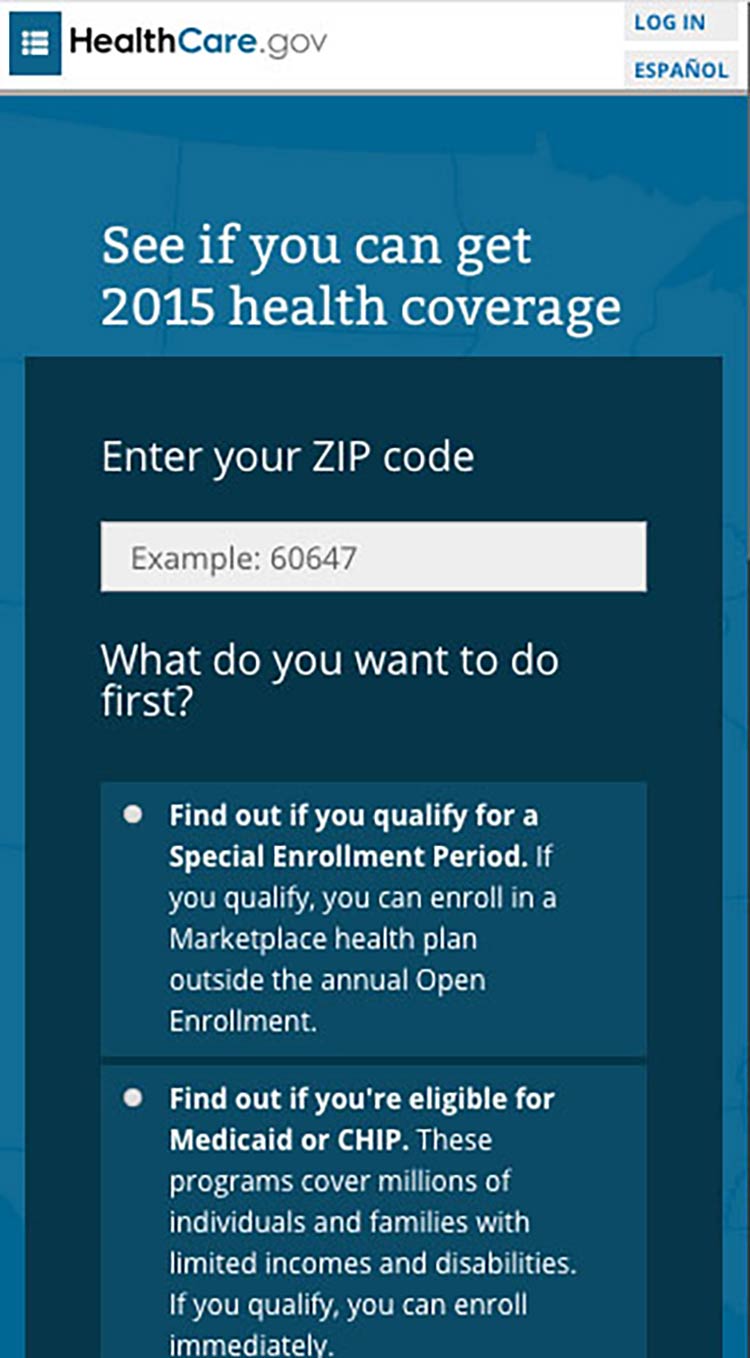

- Try radio buttons. Limited-literacy users find large radio buttons the

easiest way to make selections on a mobile device. Use them instead of

checkboxes or interactive icons.

Figure 3.16

HealthCare.gov uses radio buttons for the answers to the

question, “What do you want to do first?”

Try this

To improve “tappability,” be sure the label is associated

with the radio button. That way, the label will be tappable, too—so

users have a bigger area to tap.

Summary

To be successful, web content doesn’t just need to be well written—it

needs

to look

easy to read. Thoughtful design and layout can help your readers focus

on your content without feeling overwhelmed, confused, or distracted by

how the information is presented.

Remember to think about all your users—including those on mobile and

those with accessibility needs—when you’re designing your site. Make

sure your content is accessible and easy to navigate, regardless of how

it’s accessed.

In the next section, we discuss content organization and navigation—that

is, making sure your users can easily get to the right page on your site

to find the information they’re looking

for.