1. What We Know About Users with Limited Literacy Skills

Introduction

There’s a growing body of literature related to the cognitive processing

and online behavior of adults with limited literacy skills. In this

section, we outline what we know about how literacy can affect a user’s

ability to read, process information on a screen of any size, and

interact with technology.

The bottom line: Literacy skills can impact virtually every aspect of

using the web.

1.1 Reading and cognitive processing challenges

Cognitively speaking, reading is a lot of work—it involves both decoding

and understanding text. First, a user has to “decode” the text by

assigning meaning to the words. Next, a user has to comprehend the text

by stringing the words together to understand what the author is trying

to communicate in a particular sentence or

paragraph.1,2,3

Users with limited literacy skills have more problems with short-term

and working memory than users with higher literacy

skills.4 They may struggle to decode challenging words

and remember their meanings.3 If a webpage has a large

amount of content, users may not be able to remember it all.

Furthermore, what they do remember may not be the most important

information.

Users with limited literacy skills often describe themselves as reading

well or very well.3,5 However, data from

eye-tracking and usability studies paint a different picture.

According to these studies, users with limited literacy skills generally

read more slowly, and reread words, sections, or elements on a website

(like buttons or menus) in order to understand them.3

And depending on the situation, limited-literacy users may:

- Skip words or sections, or start reading in the middle of a

paragraph3,7,8,9

- Try to read every word because they can’t effectively scan and draw

meaning from

content3,7,10—this is

more common when users are reading something very important and they

feel the stakes are high

These strategies used by users with limited literacy skills reinforce

the importance of creating simple content that won’t overwhelm readers

with too many words. Dense “walls of words” can trigger limited-literacy

readers to skip content altogether—or they may try to read every word on

the page while struggling to understand what they’re reading.

Additionally, online forms present a unique set of challenges for

limited-literacy users. Users need to read the instructions and the form

field labels, and then either spell the answers to questions or read and

select from multiple-choice answers.3 This is a lot to

ask from users with limited literacy skills.

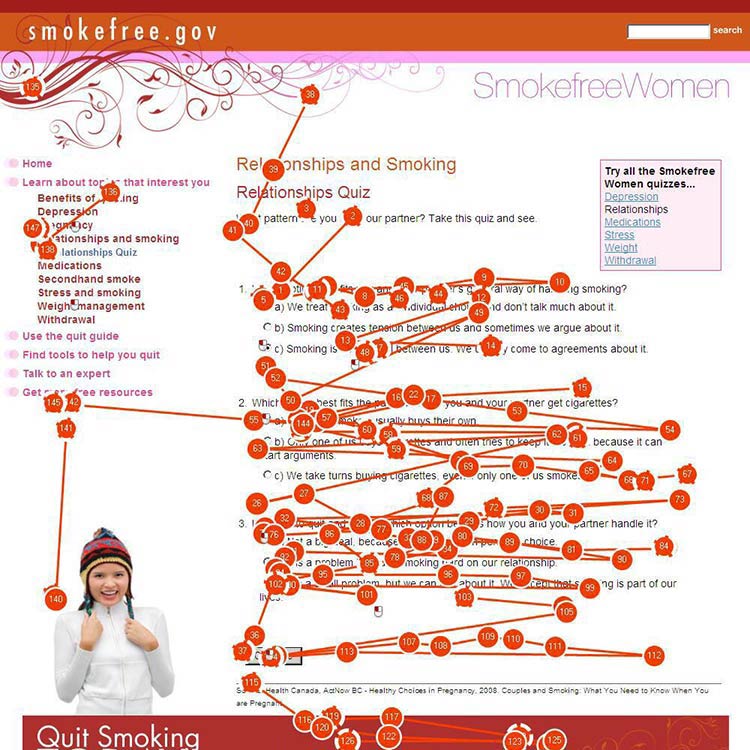

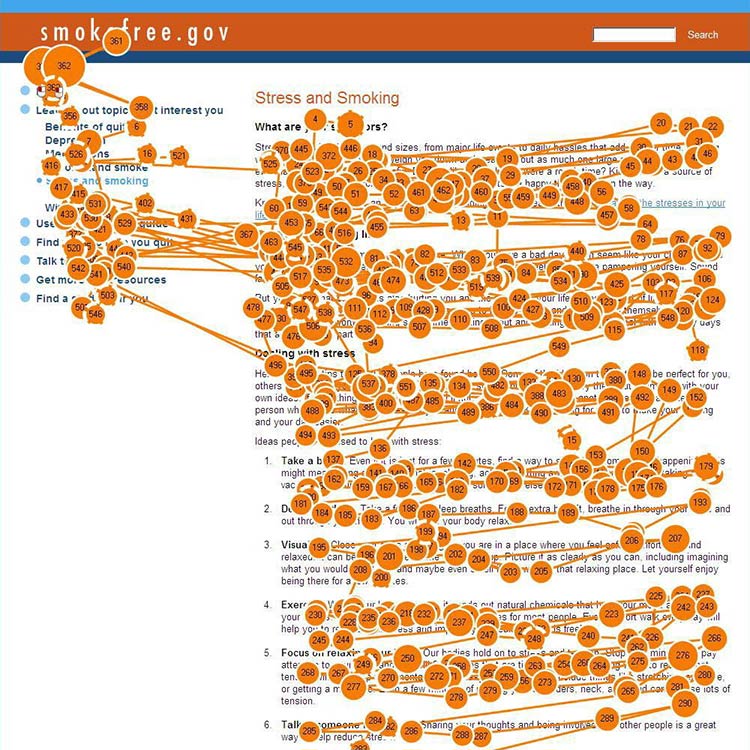

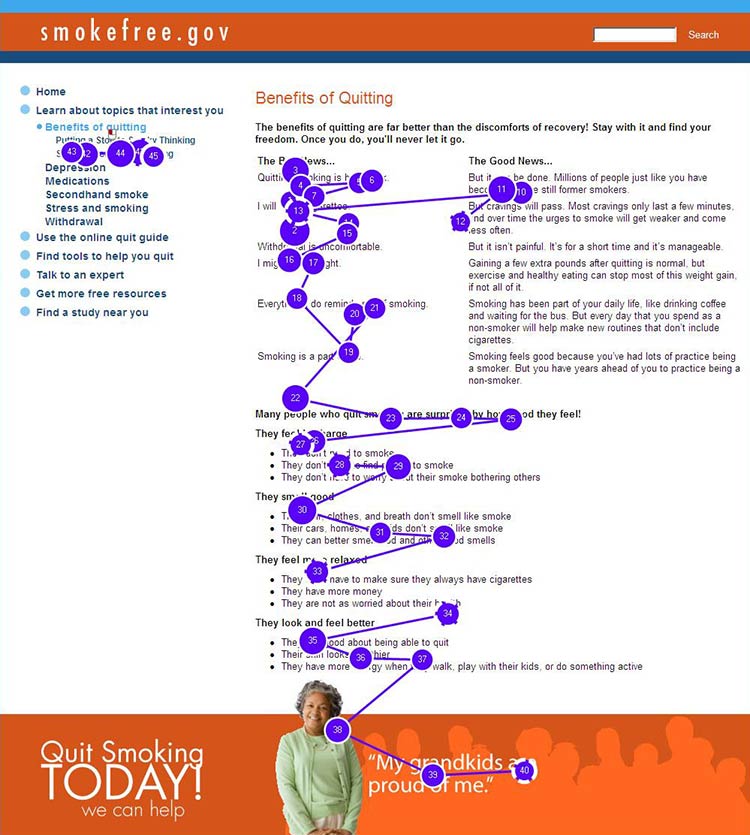

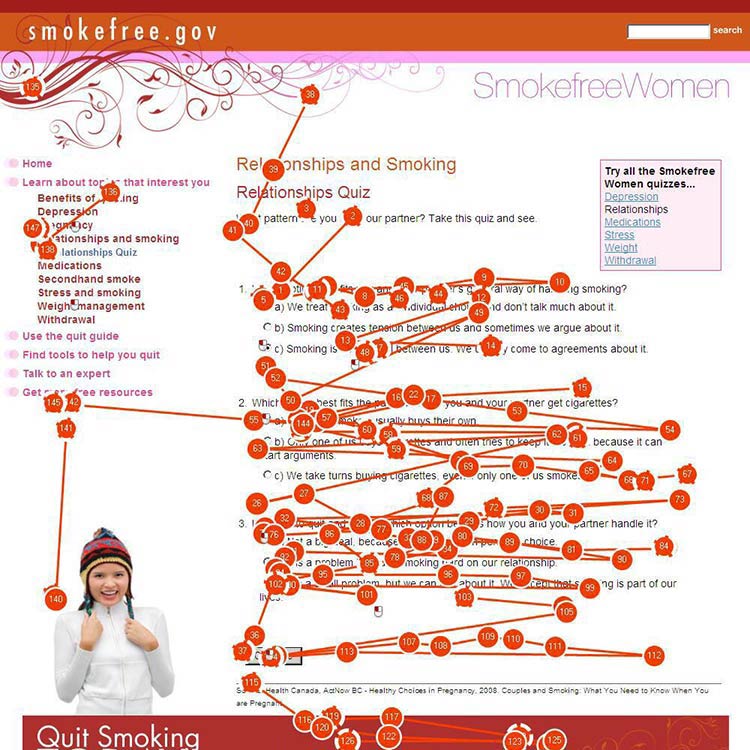

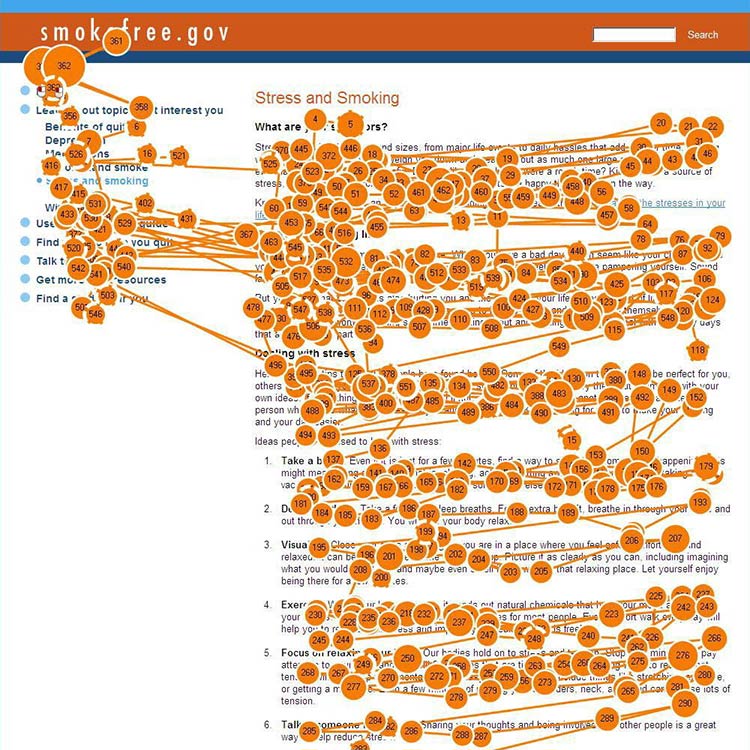

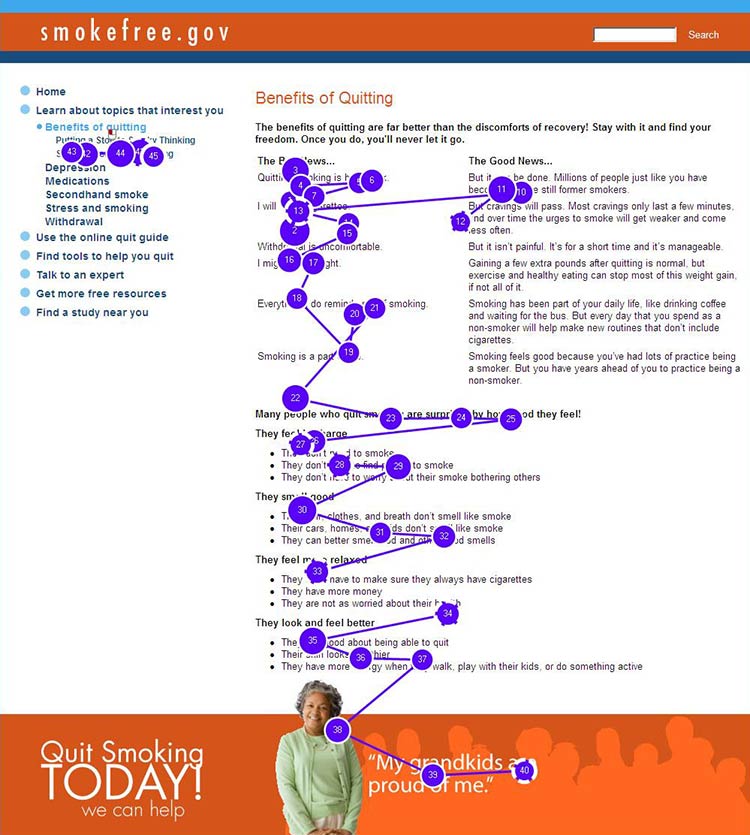

Figure 1.1

Gaze path of a reader who does not have limited literacy skills skimming a page.

Figure 1.2

Gaze path of a user who has limited literacy skills reading (and re-reading) every word.

Figure 1.3

Gaze path of a user with limited literacy skills reading only the text that looks easy to read.

1.2 Understanding navigation

When navigating a website, users with limited literacy skills tend to:

- Get distracted by extra words and elements of a website (like links

and icons)3,11

- Navigate in a linear fashion and backtrack

frequently4,10

- Choose the first answer they find, without checking if it’s

correct—and have a hard time telling the difference between high-

and low-quality

information3,10,12

- Have trouble recovering from mistakes10

When reading, users with limited literacy skills focus on the center of

the screen. Once they shift their focus from the navigation to the

center of the screen, they’re unlikely to look back to the navigation to

solve a problem or change course if the content isn’t meeting their

needs.10,13

1.3 Using search

Using a website search function can be challenging for people with

limited literacy skills. Typing in a search term requires (somewhat)

accurate spelling—and some search engines help with spelling better than

others. Reading and comparing search results to identify the best option

is a cognitively challenging task.

As a result, compared with users with advanced literacy skills, users

with limited literacy skills:

- Spend more time on information search

tasks3,10

- Are more likely to give up if they can’t find information

quickly10

- Have a hard time thinking of search terms14

- Tend to only click 1 or 2 links in the search

result14

- Add terms to refine a search instead of changing their search

strategy15

The ways people with limited literacy skills tried to find information

differ from user to user.10

Example

In previous healthfinder.gov usability testing, the team observed 5

users while they searched for information in 5 completely different

ways. Some used the left navigation menu, while others used the homepage

buttons or the search bar.

1.4 Mobile considerations

Users with limited literacy skills are likely to access the web on

mobile devices—more than 90% own a mobile phone.16 We

also know that users with lower incomes, users with less education, and

minority users are especially likely to access the internet primarily

from their mobile phones.17

Research shows that people with limited literacy skills find it easier

to learn how to use mobile devices than desktop

computers.18

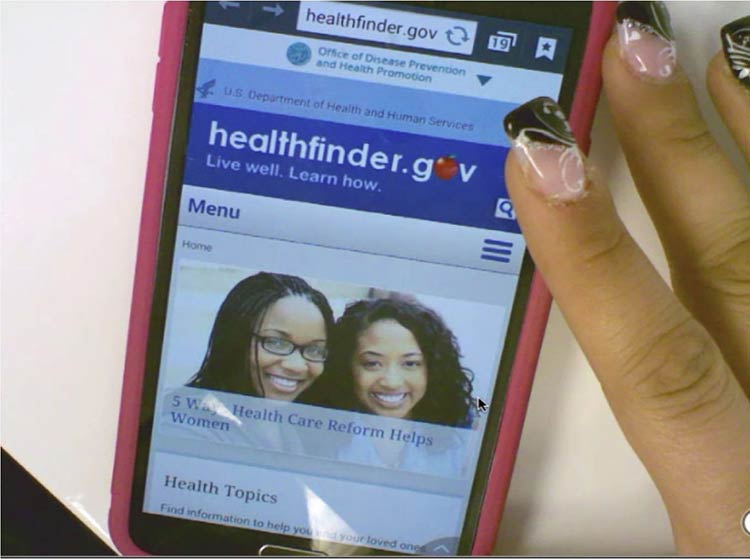

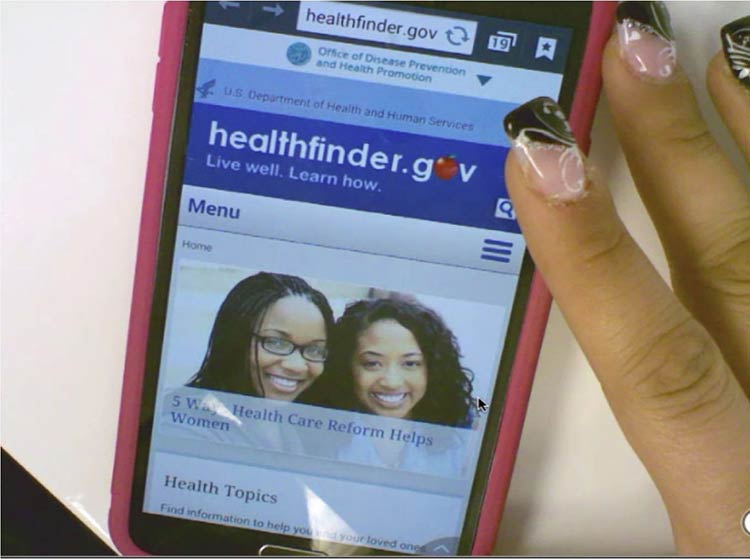

Figure 1.4

When we tested healthfinder.gov on mobile in March 2015, users navigated through health topics much more easily on their mobile devices than on a desktop computer.

Additionally, mobile screens can make reading easier for users with

reading disabilities. For this population, both speed and comprehension

may improve when reading on a mobile screen. Studies suggest this may be

because of line length—lines on mobile devices are inherently

short.19

All of the best practices set forth in this guide enhance mobile

usability. However, there are some specific considerations to take into

account when designing online health information for mobile devices.

Challenges of mobile display

Because we know that so many users with limited literacy skills are

accessing information on mobile devices, it’s very important to consider

the challenges presented by mobile display.

In spite of the fact that many users with limited literacy skills may

ultimately find mobile easier to use than desktop computers, they still

struggle with elements of navigation on mobile devices, like:

- Following hierarchical navigation

- Knowing where to look for information

- Using scroll bars within menus

- Using a single button (like the iPhone menu button) for a variety of

different purposes depending on context

- Using a small keyboard to enter text20

In general, mobile content can be twice as difficult for all users to

digest.21 Part of this is because it’s harder to

understand complicated information when you’re reading on a tiny screen,

like an iPhone.21

Additionally, mobile device users are constantly scrolling because they

can’t see all the information on the page at once. That means users are

moving around the page to refer to other parts of the content instead of

simply glancing at it as they might on a desktop screen. This can

negatively affect users’ understanding.22 The constant

need for scrolling:

- Takes more time

- Diverts users’ attention

- Introduces the problem of reorienting position on the

page22

Summary

It’s critical that we understand and anticipate the online behavior of

users with limited literacy skills—including what kind of devices

they’re using to view web content. Even users with high literacy skills

may find reading and using the web more difficult when they are sick,

stressed, or tired. Designing websites with these behaviors in mind will

make the web a better place for all of us.23

On the journey to better user experience, simplifying content is a

logical place to start.

In the next section, we cover the basics of writing actionable, engaging

plain language content for the web.